This post was originally published as a November 16, 2017 article on MeetingsNet.

The Medicare Access and Chip Reauthorization Act of 2015, a congressional effort to solve the riddle of how to pay physicians under the Medicare program, does more than move what has traditionally been a fee-for-service model to a value-based model. It also just may offer some new areas of opportunities for continuing medical education.

Andy Rosenberg, senior advisor with the lobbying group the CME Coalition, laid out just what MACRA is—and why CME providers should be paying attention to it—in a recent MeetingsNet webinar.

What MACRA Is

Calling the effort to fix a flawed Medicare reimbursement mechanism “remarkable,” Rosenberg said MACRA moves from a system that had based reimbursement on the number of services physicians provided, to one that reimburses based on physicians providing value.

He explained that MACRA’s core idea came out of an article written by Donald Berwick in 2008 in Health Affairs; Berwick subsequently became the administrat or of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS. In the article, he outlined what he called the “triple aim” of healthcare:

“It seems easy, right? Let’s just start reimbursing providers for better quality, rather than just for providing more services,” Rosenberg said. But defining value depends on who you are—insurance payor, health system, provider, doctor, or patient.

So, he said, this begs a few questions. “How do we measure quality? How do we value innovation? How do we make sure that we are being patient-centered, which means that we are actually allowing patients to define what they consider valuable? How do we develop quality measures by which to measure the performance of doctors and hospitals?” It turns out that improving quality is not straightforward at all; in fact it’s pretty confusing.

Part of a Broader Trend

Rosenberg stressed that it’s important to note that what CMS is doing in driving value-based care is part of a broader industry trend towards value-based purchasing. For example, in the pharmaceutical space, a pharmaceutical company may have an expensive new product, but insurers only want to pay for that product if they know it will get results. “This is a whole new area of interpreting and determining value, and setting the terms for reimbursement based upon a treatment’s success at actually achieving those goals.”

Say one of those goals is reduced hospitalization. “A hospital system or an insurer might enter into an agreement for a certain drug or to put a certain drug on formulary. The amount that that payor will actually pay the drug company will depend upon the performance of patients that are on that treatment.” Another example he shared is a recent drug that may potentially be able to cure a form of pediatric cancer. They are in the process of entering into agreements where, if the patient is not still alive after treatment or doesn’t show progress after a year, the company will reimburse the full cost of the drug, he said.

Thomas Sullivan, founder and president of medical education company Rockpointe Corp., added that it’s also important to keep in mind that this trend is affecting more than just Medicare and other U.S. government programs—private payors also are embracing it.

“Part of our job as educators is to teach physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and other healthcare providers—basically the whole system—how to deliver this value of care,” he said. “That’s really the role of the meetings. How do we use parts of our meetings to teach not just the science, but also how the science applies to improving the value of care so they don’t lose out on the reimbursement that this train is moving towards.”

MIPS Payment Paths

To drive doctors under Medicare to practice the kind of medicine that will result in better quality rather than simply more services, MACRA provides two payment paths for doctors. One provides higher Medicare reimbursements for doctors who take part in what’s called an “alternative payment model”—a universal service healthcare provider system that only applies to about 5 percent of doctors currently.

The second path is called MIPS, which stands for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System. Under MIPS, starting in 2017 doctors are encouraged to begin to participate in the QPP, Quality Payment Program, by either receiving demerits and reductions, or bonuses in reimbursements, based upon their performing a certain quality measure or participating in improvement activities that are approved by CMS, said Rosenberg.

“All of a sudden, doctors who want to see their reimbursement level stay steady, if not increase, are going to become very attuned to how to practice medicine in such a way that they are meeting the goals CMS is providing,” he said. “By the way, this is all going to ramp up over the next couple of years. This was CMS’s effort to allow doctors to begin to test the waters and learn how to use this system to get credit. I don’t have to tell you that doctors have reacted, by and large, with concern about how to participate in this.”

Doctors had four main options to get there.

“Over the coming years, these are only going to ramp up and up with greater and greater incentives for doctors to follow the improvement activities and quality measures that CMS is laying out for them,” he said.

While doctors have a number of different boxes they’ll need to check to hit these different tiers of reimbursement, Rosenberg said, “What’s important for us is that starting in 2017, going all the way through 2021, 15 percent of their score will depend on whether or not they are meeting the CMS expectation of performance of improvement activities.”

The CME Angle

CMS identified more than 90 improvement activities ranging from participation in Patient-Centered Medical Home care-delivery model to extra office hours. But how to get CME into the mix?

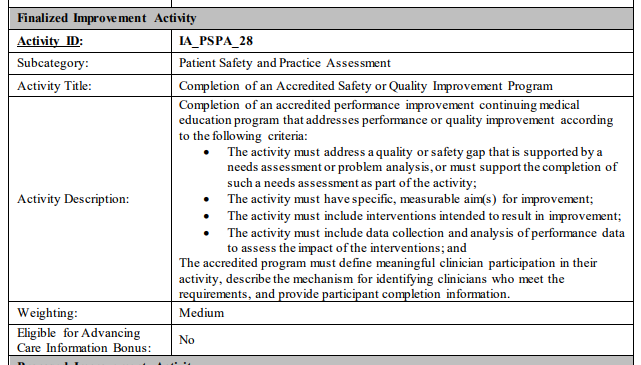

A CME working group that includes the Accreditation Council for CME, the Alliance for Continuing Education in the Health Professions, the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the Council of Medical Specialty Societies, and other medical specialty societies got together to design and submit a proposed medium-weighted improvement activity for quality-improvement CME.

According to Sullivan, “We said, ‘Hey, we need to have an improvement activity that includes CME, because they’re not going to be implementing something that they’re not getting credit to learn how to do, especially because it takes so much time to learn how to do it.’ We’ve gotten together and worked with CMS to get that approved.” It was adopted by CMS in the proposed rule in June; the final MACRA rule for 2018 was released on November 2. The improvement activity we proposed was adopted as written.

For CME activities to be considered an improvement activity, they have to address a quality or safety gap that is supported by a needs assessment or problem analysis. The activity also must have specific measurable aims for improvement, or outcomes. Sullivan added, “You must have a measurable aim, such as lowering A1C in diabetics by one percentage point.” The activity also has to include interventions intended to result in improvement, collect and analyze performance data to assess the impact of the interventions, and it must define what constitutes meaningful clinical participation.

“Basically, MACRA is really about data and measurement,” said Sullivan. “We’re teaching physicians how to use their own data for clinical quality improvement.” The MACRA QI CME activity can be combined with other improvement activities, such as data registry and some claims data activities, he added. “It can count towards other things and contribute up to 40 percent of a physician’s composite performance score for earning more than the fee schedule reimbursement.” These activities also can qualify for Maintenance of Certification Parts 2 and 4.

“For the first time, physicians will get credit for learning how to do what the government has told them that they absolutely need to do—and what are other payors are going to be asking for in the future.”

Note: The Quality Payment Program final rule with comment period (CMS-5522-FC and CMS-5522-IFC) can be downloaded from the Federal Register here.

For a fact sheet on the Quality Payment Program final rule with comment period, please visit cms.gov.

Andy Rosenberg, senior advisor with the lobbying group the CME Coalition, laid out just what MACRA is—and why CME providers should be paying attention to it—in a recent MeetingsNet webinar.

What MACRA Is

Calling the effort to fix a flawed Medicare reimbursement mechanism “remarkable,” Rosenberg said MACRA moves from a system that had based reimbursement on the number of services physicians provided, to one that reimburses based on physicians providing value.

He explained that MACRA’s core idea came out of an article written by Donald Berwick in 2008 in Health Affairs; Berwick subsequently became the administrat or of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS. In the article, he outlined what he called the “triple aim” of healthcare:

- Providing better care for individuals in terms of safety, effectiveness, patient centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity.

- Improving the health of populations by attacking what he called the “upstream” causes of ill health such as poor nutrition, physical inactivity, and substance abuse, said Rosenberg.

- Reducing the per capita costs of healthcare

“It seems easy, right? Let’s just start reimbursing providers for better quality, rather than just for providing more services,” Rosenberg said. But defining value depends on who you are—insurance payor, health system, provider, doctor, or patient.

So, he said, this begs a few questions. “How do we measure quality? How do we value innovation? How do we make sure that we are being patient-centered, which means that we are actually allowing patients to define what they consider valuable? How do we develop quality measures by which to measure the performance of doctors and hospitals?” It turns out that improving quality is not straightforward at all; in fact it’s pretty confusing.

Part of a Broader Trend

Rosenberg stressed that it’s important to note that what CMS is doing in driving value-based care is part of a broader industry trend towards value-based purchasing. For example, in the pharmaceutical space, a pharmaceutical company may have an expensive new product, but insurers only want to pay for that product if they know it will get results. “This is a whole new area of interpreting and determining value, and setting the terms for reimbursement based upon a treatment’s success at actually achieving those goals.”

Say one of those goals is reduced hospitalization. “A hospital system or an insurer might enter into an agreement for a certain drug or to put a certain drug on formulary. The amount that that payor will actually pay the drug company will depend upon the performance of patients that are on that treatment.” Another example he shared is a recent drug that may potentially be able to cure a form of pediatric cancer. They are in the process of entering into agreements where, if the patient is not still alive after treatment or doesn’t show progress after a year, the company will reimburse the full cost of the drug, he said.

Thomas Sullivan, founder and president of medical education company Rockpointe Corp., added that it’s also important to keep in mind that this trend is affecting more than just Medicare and other U.S. government programs—private payors also are embracing it.

“Part of our job as educators is to teach physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and other healthcare providers—basically the whole system—how to deliver this value of care,” he said. “That’s really the role of the meetings. How do we use parts of our meetings to teach not just the science, but also how the science applies to improving the value of care so they don’t lose out on the reimbursement that this train is moving towards.”

MIPS Payment Paths

To drive doctors under Medicare to practice the kind of medicine that will result in better quality rather than simply more services, MACRA provides two payment paths for doctors. One provides higher Medicare reimbursements for doctors who take part in what’s called an “alternative payment model”—a universal service healthcare provider system that only applies to about 5 percent of doctors currently.

The second path is called MIPS, which stands for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System. Under MIPS, starting in 2017 doctors are encouraged to begin to participate in the QPP, Quality Payment Program, by either receiving demerits and reductions, or bonuses in reimbursements, based upon their performing a certain quality measure or participating in improvement activities that are approved by CMS, said Rosenberg.

“All of a sudden, doctors who want to see their reimbursement level stay steady, if not increase, are going to become very attuned to how to practice medicine in such a way that they are meeting the goals CMS is providing,” he said. “By the way, this is all going to ramp up over the next couple of years. This was CMS’s effort to allow doctors to begin to test the waters and learn how to use this system to get credit. I don’t have to tell you that doctors have reacted, by and large, with concern about how to participate in this.”

Doctors had four main options to get there.

- Penalty Avoidance. Between January 1 and October 2 of 2017, doctors had to provide 90 days of data to avoid penalty under their current Medicare reimbursement level. To do that, they need to have performed one CMS-approved quality measure, one clinical practice improvement activity, or five required advancing care information measures, and submit the data by March 31, 2018.

- Delayed Start. The submission due date for this option is also March 31, 2018, and it is also based on 90 days of data collected between January 1 and October 2, 2017. The requirements include doing at least one quality measurement, and at least an improvement activity and/or five advancing care information measures. While it does require more work—“They have to demonstrate that they’ve checked more boxes”—physicians can increase their reimbursement from between 2 percent and 4 percent under Medicare, said Rosenberg.

- Ready to Go. If doctors have done six quality measures over this same time period, and four general improvement activities or two for small, rural, Health Resources and Services Administration, or non-patient-facing improvement activities, they can receive as much as 4 percent above what they normally would receive, he said.

- There is a fourth option that is even more advantageous for that 5 percent in the Alternative Payment model.

“Over the coming years, these are only going to ramp up and up with greater and greater incentives for doctors to follow the improvement activities and quality measures that CMS is laying out for them,” he said.

While doctors have a number of different boxes they’ll need to check to hit these different tiers of reimbursement, Rosenberg said, “What’s important for us is that starting in 2017, going all the way through 2021, 15 percent of their score will depend on whether or not they are meeting the CMS expectation of performance of improvement activities.”

The CME Angle

CMS identified more than 90 improvement activities ranging from participation in Patient-Centered Medical Home care-delivery model to extra office hours. But how to get CME into the mix?

A CME working group that includes the Accreditation Council for CME, the Alliance for Continuing Education in the Health Professions, the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the Council of Medical Specialty Societies, and other medical specialty societies got together to design and submit a proposed medium-weighted improvement activity for quality-improvement CME.

According to Sullivan, “We said, ‘Hey, we need to have an improvement activity that includes CME, because they’re not going to be implementing something that they’re not getting credit to learn how to do, especially because it takes so much time to learn how to do it.’ We’ve gotten together and worked with CMS to get that approved.” It was adopted by CMS in the proposed rule in June; the final MACRA rule for 2018 was released on November 2. The improvement activity we proposed was adopted as written.

For CME activities to be considered an improvement activity, they have to address a quality or safety gap that is supported by a needs assessment or problem analysis. The activity also must have specific measurable aims for improvement, or outcomes. Sullivan added, “You must have a measurable aim, such as lowering A1C in diabetics by one percentage point.” The activity also has to include interventions intended to result in improvement, collect and analyze performance data to assess the impact of the interventions, and it must define what constitutes meaningful clinical participation.

“Basically, MACRA is really about data and measurement,” said Sullivan. “We’re teaching physicians how to use their own data for clinical quality improvement.” The MACRA QI CME activity can be combined with other improvement activities, such as data registry and some claims data activities, he added. “It can count towards other things and contribute up to 40 percent of a physician’s composite performance score for earning more than the fee schedule reimbursement.” These activities also can qualify for Maintenance of Certification Parts 2 and 4.

“For the first time, physicians will get credit for learning how to do what the government has told them that they absolutely need to do—and what are other payors are going to be asking for in the future.”

Note: The Quality Payment Program final rule with comment period (CMS-5522-FC and CMS-5522-IFC) can be downloaded from the Federal Register here.

For a fact sheet on the Quality Payment Program final rule with comment period, please visit cms.gov.